This past Oscars gave me plenty to be hopeful about while it still creates further detachment from the art of film. Al Pacino stumbled in to quickly deliver Best Picture in a manner so truncated I can only appreciate it, and it wasn’t his fault. It was a fitting anticlimax for a night that left little room for surprise, as Oppenheimer was sure to claim the award because of its passionate fans and box office power. One may wonder if the film would have had a shot at the award if it didn’t have the box office numbers to back it, but such a spectacle of unrelenting and empty change is perfect for an Academy that prefers something that overrides any momentary reaction. Oppenheimer is sometimes described as people mostly talking for three hours; I would have preferred to see such a film. Its maximalist onslaught on the senses bars any chance of interacting with its issue of destiny. Instead, Cillian Murphy’s certified Best Actor blue eyes are a vacuum that cannot be deciphered. Viewers are left to wake up after these three hours and ask, “What have I just watched?” The only way to satisfactorily answer this is by praising it as a masterpiece of craft. Hence, its overall triviality perfectly lends itself to TikTok cinema where its score can generate billions of social media impressions. Oppenheimer makes no effort to understand its unknowability and happily plunges into an abyss of failure, ultimately thoughtless. It is possible to become blind and deaf watching it.

However, there is some comfort in the increased recognition of international cinema at the ceremony. The Zone of Interest took more than Best International Feature, also being awarded for Best Sound. The Boy and the Heron won for Best Animated Feature, and 20 Days at Mariupol won for Best Documentary Feature in a category that was remarkably made up of all non-US films. Anatomy of a Fall won Best Original Screenplay, and Godzilla Minus One won Best Visual Effects. These acknowledgments are further reflective of the possibilities revealed when the first film not in English to win Best Picture, Parasite, won in 2020. Since, the Academy and audiences have trended towards watching more international cinema—slowly and perhaps not always straightforwardly.

Engaging with a varied cinema can be difficult when getting started. My film upbringing consisted mostly of Hollywood spectacles like Star Wars and Indiana Jones, film franchises at one point that may have had merit but now only exist through manipulated sentimentality of nostalgia. The commerciality of Hollywood productions overpowers much of what is distributed across the country and the rest of the world, taking up most screens. The entertainment of “giving the people what they want” is set by the conditioning of Hollywood narrative, in reality giving the people what we have been told to want. I think this is extremely clear in the success of Top Gun: Maverick.

As New Yorker critic Richard Brody points out, “Maverick’s assignment is to train a dozen young ace pilots for a top-secret and crucial mission, to fly into a mountainous region in an unnamed ‘rogue’ state and destroy a subterranean uranium-enrichment plant.” This realizes militaristic fantasy for audiences and the producers behind blatant propaganda. While it remains undeniably immersive as the viewer succumbs to the excitement, there is a darker reality underneath. The “unnamed” quality of Top Gun: Maverick helps us to imagine taking down the target of any contemporary foreign adversary of the US military; it can be the Taliban in the 2000s, ISIS in Syria, or any communist nation that can fulfill the suppressed rage of the Cold War’s aftermath. At the very least, we are assured that pure good triumphs over an unnuanced evil. Such a reading of a limited Hollywood is by no means original but should be reiterated many times, as American influence on cinema worldwide can also not be understated.

With a film like Top Gun: Maverick, we begin to see the necessity to expand viewing to other nations’ films and experience new perspectives on affairs extreme and minute. This is what it’s all about: people trying to see more of the world than what is possible by only going to see every new blockbuster. International films cannot directly replace the tangibility of travel, but an inclusive contemplation of cinema can help us understand more of the world and ourselves.

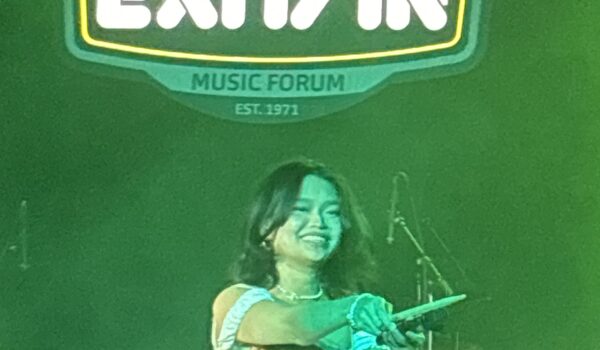

Making this a reality is fortunately possible with student streaming access and nearby programming at the Belcourt. The Belcourt is currently in the middle of Passports: An International Film Series. This has already shown many great new films like Pictures of Ghosts, Here, and About Dry Grasses. While almost done, there is still the highly anticipated Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World left, a Romanian film that has received great acclaim. Even when the series ends, the Belcourt always has more international films new and old in its lineup.

Becoming comfortable with different methods of cinema is tough, and I am not perfect when it comes to this either. It is easy to fall back into unthreatening habits when it has been the norm for so long. While watching, it is tempting to look for familiar conventions and appreciate films that conform, or we yield and try to project conformity back onto the screen. This can be best treated by further watching and overcoming, so here are a few recommendations to get started or if you’re already familiar and simply curious.

Quo Vadis, Aida? (Hulu, Bosnian, Serbian, 2020)

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Academic Video, Spanish, 1988)

Senso (Max, Italian, German, 1954)

Bacurau (Kanopy, Portuguese, 2019)

Close-Up (Kanopy, Persian, 1990)

The Spirit of the Beehive (Kanopy, Spanish, 1973)

Fallen Angels (Kanopy, Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese, 1995)

The Gleaners and I (Kanopy, French, 2000)

These films are best to experience for yourself without any descriptive interference from me. All I’ve mentioned are the films’ streaming, primary languages (although others are sometimes used outside what is mentioned), and release year. I think if anyone were to watch every film in this list, they would find at least one movie they would enjoy that could encourage them to explore more films from whatever decade, region, or language is connected to it.

Comments